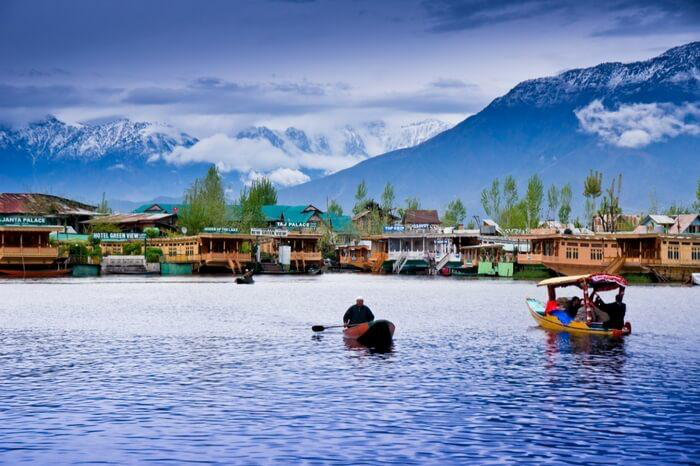

Kashmir has been integral to the Indian identity for millennia. Its rich culture, enlightening scholarship, and natural beauty have contributed greatly to the nation’s framework. Yet, the very fabric of Kashmir has been pulled apart, thread by thread, since the 1300s as a result of invasion. A region known for its pristine landscape of snow-capped mountains and numerous waterfalls has fallen victim to bubbling turmoil and radical fundamentalist-based violence.

What was first a haven to Kashmiris of diverse faiths and beliefs transformed into a region of terror, intolerance, and massacre. The Kashmiri Pandits, an indigenous Hindu population, have faced a fate that is difficult to truly portray with words. In order to understand what they experienced, it is important to understand the history of Kashmir and its people, including the political motives of surrounding nations.

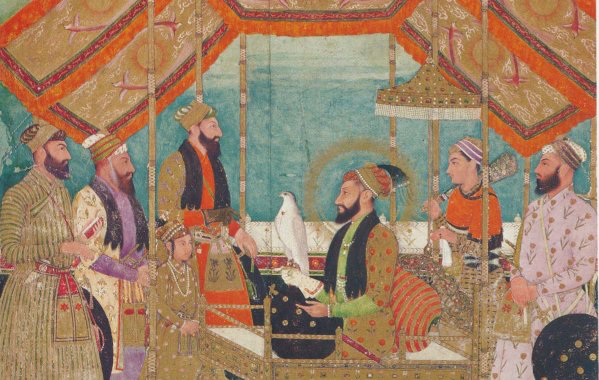

Kashmir is the birthplace of many Hindu and Buddhist teachings, including Kashmiri Shaivism. Much of its earlier history is accounted for in Hindu texts including Nilamata Purana and Kalhana’s Rajatarangini. In the 14th century, invaders from Central Asia attacked Kashmir and began the Islamization of the region. The fall of the Lohara dynasty made Kashmir vulnerable and a Turkic-Mongol ruler, Zulju, led a rampant takeover of the area. What was once the home of a Hindu and Buddhist majority became a vehicle for mass-conversion, especially under the rule of Shah Mir. As Islam became the dominant-faith in Kashmir, what was once a hub for Sanskrit teachings became silent. The reign of Sultan Sikandar introduced taxes on non-Muslims and destroyed countless Hindu idols. In the 1500s, Hindu representation in courts declined and missionaries continued to flood the region. Sanskrit was replaced by Persian as the official language. Over the years, Kashmir continued to be tossed around from Mughal rulers to the Sikh empire at the expense of the Kashmiri people.

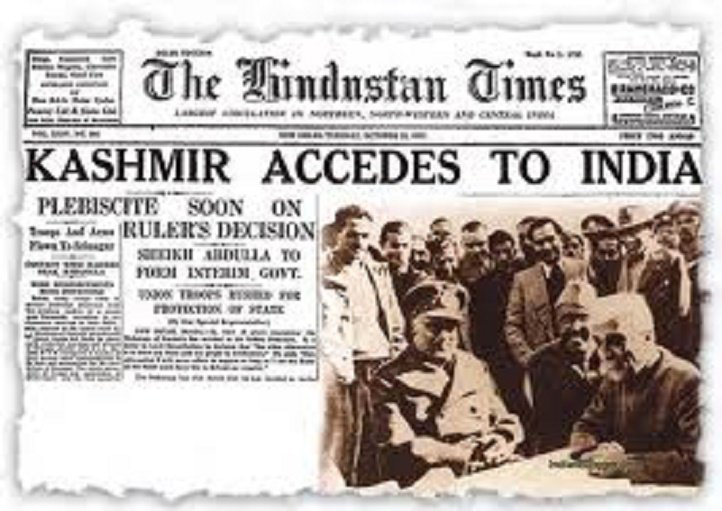

In 1947, the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir was ruled by Hari Singh. This year marked the end of British rule and the partition of Pakistan as an Islamic Republic from secular India. Hari Singh was responsible for determining Kashmir’s accession to India or Pakistan. It was during this time that radical warriors from Pakistan began rioting in Kashmir, killing and looting civilians regardless of faith. These tribesmen aimed to frighten Hari Singh into submission, yet their violence led Hari Singh to request India for assistance and led him to sign the Instrument of Accession to India.

Indian soldiers were able to push back the Pakistani radicals for the most part, yet a section of Kashmir continued to be occupied by them. India approached the United Nations to resolve the conflict and they proposed a 3-step referendum. First, Pakistan must withdraw Pakistani intruders from the portion of Kashmir they continue to illegally occupy. Then, India must confirm that Pakistan has retreated and later reduce Indian forces in the region. Finally, the accession of Kashmir to India or Pakistan will be decided by a free and impartial plebiscite. Pakistan has failed to complete the first step to this day and there have been three wars over Kashmir since the partition. Over the course of time, the plebiscite became more irrelevant as accords were put into place. The Indira-Sheikh Accord signed in 1975 acted as a resolution to previous political qualms between Sheikh Abdullah and the Indian government. It gave Abdullah the position of “Chief Minister” over the state of Jammu and Kashmir and allowed Kashmiris to exercise free democracy in following elections, mirroring the processes in Indian state governments.

After the mass conversion of Kashmiri Hindus to Islam over the centuries, a small population of Kashmiri Hindus remained in the valley, known as Kashmiri Pandits. By 1981, the Pandit population dwindled to a bare 5% (Our Moon Has Blood Clots, 255). Radical Islamic insurgency increased as terrorists swept the region. Temples were destroyed and anti-Hindu slogans were played over loud-speakers from mosques. Their goal was to eradicate any non-Muslims in Kashmir and therefore illegally acede the entirety of Kashmir to Pakistan. On September 14th, 1989, Kashmiri Pandit Tika Lal Taploo was assassinated. He was a leader in the community and his murder marked the beginning of the horrific fate of Hindus in Kashmir. Kashmiri Pandits experienced 7 exoduses total, the most violent being on January 19th, 1990. Hizbul Mujahideen, a pro-Pakistani militant group deemed to be a terrorist organization by India, the European Union, and the United States, published a press release in various newspapers demanding all Hindus to leave the valley. This press release was soon printed and pasted on every Kashmiri Pandit’s front door.

On January 19th, the air of the Kashmir valley was heavy with the smells and sounds of hatred. Islamic terrorists filled the night with yells, screaming Kashmir banega Pakistan Pandit admiyon ke beghar, par Pandit oratho ke saath (Kashmir will become part of Pakistan without Pandit men, but with Pandit women), Agar Kashmir mein rehna hai, Allahu Akbar kehna hoga (If you would like to remain in Kashmir, you must chant Allah is the greatest), and other extremist, bigoted, and intolerant slogans. The fears of Kashmiri Pandits became tangible as their own Muslim neighbors who they had shared classrooms, dinners, and gatherings with joined in. Many Kashmiri Pandits fled the valley for their lives as terrorists marched into villages with large guns and other weapons, leaving their homes, memories, and livelihoods behind. Some Kashmiri Pandits hid in abandoned buildings while others took shelter in large rice barrels and barns. The radicals went home to home, torching everything on fire and shooting any Kashmiri Pandit in sight. Hindu women were told to stay hidden if the building they were in was inflamed because death would be preferred over a lifetime of rape and assault. Many men were tortured before being killed, as their eyes were gouged and genitals cut off. Even newborn babies were not spared. The land that held the history of Kashmiri Pandits over thousands of years was soon soaked with their innocent blood.

WARNING, GRAPHIC IMAGE Click here to scroll past

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

SCROLL TO HERE TO SKIP GRAPHIC IMAGE

Those that escaped the valley took refuge in Jammu. The next morning, many learned of their slaughtered parents, aunts, uncles, children, neighbors, friends, and teachers. A sadness and sense of loss so dark and so deep settled within the hearts of Kashmiri Pandits. Their lives were snatched from them by Islamic radicals. All they had left were memories. As news of what had occurred crept into the rest of India, little to no action was taken. The rest of the world remained silent, too. News outlets avoided printing anything out of fear and ignorance, and the government of the time did not provide any support to the Kashmiri Pandit population. Many were forced to live in small, shabby tents with no privacy and deadly illnesses traveled quickly around the grounds. Venomous snakebites were common and many Hindus died from famine and heat stroke as they were accustomed to the cooler climate of the valley. There was no way the Kashmiri Pandits could return home. We would be killed. As refugees in our own country, the remaining 400,000 Kashmiri Pandits were forced to start life anew.

Without any money or connections, it was extremely tough for Kashmiri Pandits to find jobs, get a formal education, or purchase land. Optimism was not in our vocabulary — we had witnessed death and despair. Our only source of motivation was each other. Radicals may have kicked out Kashmiri Pandits out of Kashmir, but they could never take Kashmiriyat, or the Kashmiri identity, from us. We had always lived a virtuous life of peace, honesty, and responsibility and used these values to start over. We soon began to use our talents to create a basic income, ranging from teaching classes to creating handicrafts to cooking authentic Kashmiri food to opening small businesses. We settled in various parts of India and then around the world. The Kashmiri Hindu diaspora is small, yet strong. There is an entire generation of Kashmiri Pandits that has not once been able to visit the valley of our heritage, yet feels so close to that Kashmiriyat: Kashmiri food, music, and language tie the community together.

The year 2020 marks the 30th anniversary of that horrific day. Every moment of January 19th, 1990 will remain engrained in the memories of Kashmiri Pandits. Not a single day passes in which we do not miss our home. These hopes to return have been reignited by the current Indian government, given the abrogation of article 370. The Indian government having formal legislation over Jammu and Kashmir means a chance for us to claim the land that raised us and the possibility of radicalism to be pushed out of the region for good.

Bozeve myean kaath?

Can you hear me? Will you listen to us?

The story of Kashmiri Pandits is more important than ever in today’s discussion of global politics and the world should recognize our plight.

- by @IndigenousKashmir

For more information:

- K Pandita, Rahul (2013). Our Moon has Blood Clots: The Exodus of the Kashmiri Pandits. Vintage Books / Random House.

- http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/exodus-of-kashmiri-pandits-january-19-jammu-and-kashmir/1/574071.html

- https://books.google.com/books?id=X0QQx5ObGysC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA189#v=onepage&q&f=false

- https://books.google.com/books?id=InAwDQAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&pg=PT310#v=onepage&q&f=false

- https://www.efsas.org/publications/study-papers/the-exodus-of-kashmiri-pandits/

- https://www.rediff.com/news/2003/mar/25guest.htm

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-35923237